I have never been so happy to see a witch. With her horned skull and a presence that, according to Ron Perlman's tar-thick narration, you feel long before you see her, "like a storm rolling in," she could be the end-of-level boss in another game. In West of Dead, a roguelike set in the bleak Wild West underworld, your interactions with her are your only sustained progress.

It always begins in a tavern. No matter how deep you dive into the catacombs, the snow-covered wilderness where dogs roam, or the deepest mines of purgatory, death will spit you back here. So you dust yourself off and head back to the catacombs, with a couple of level 1 firearms as companions.

The gunfight is only just beginning. West of Dead's combat is a blend of twin-stick shooting and cover systems, with tactical innovations in several rooms, such as lights that stun nearby enemies and loot amulets that halve reload time or restore your strength if you jump into cover immediately after being hit. The game is elaborate.

There are no killer ideas like Frozen Synapse 2 or Superhot that radically reinvent shooting people. It's a simple framework that unfolds in the gloomy emptiness of West of Dead at just the right pace to keep players on their toes. The first couple of times in Crypt felt like a stumbling block, but I slowly began to appreciate the pace and nuances of the combat. How many six-shooter hits does it take to stun a gun-toting enemy, or how many hits does it take to destroy a hideout where you tend to hide yourself? I have noticed that enemies in close combat, such as zombies, tend to follow me to the front passage where they are easy to take down.

West of Dead does a masterful job of warning you of every minute detail of the battle, from the moment the enemy becomes aware of your presence to the moment he sets his sights on you. Once all the timing is pervasive, you are not playing consciously, but reflexively. Always in cover, always aware of how many empty chambers are in each gun, always looking for the next safe place to roll in. (I lament to myself that I drank out the health flask two rooms ago instead of now when I really need it.)

Both the controls and the visual feedback are clever enough that the barrier between you and what you envision yourself doing melts away. It is essential that such games feel fair and consistently legible, even though they require you to be okay with losing everything and starting over from scratch if you die. Tick and tick.

These basics are then built on as the enemy types change in each subsequent area - by the way, the hounds on the second map absolutely disappear. Especially when they involve huge bags of biceps that can kill you with a single blow from a butcher's blade, or huge bags of pus that rush at you ready to explode as soon as you get close, they can really ruin your day.

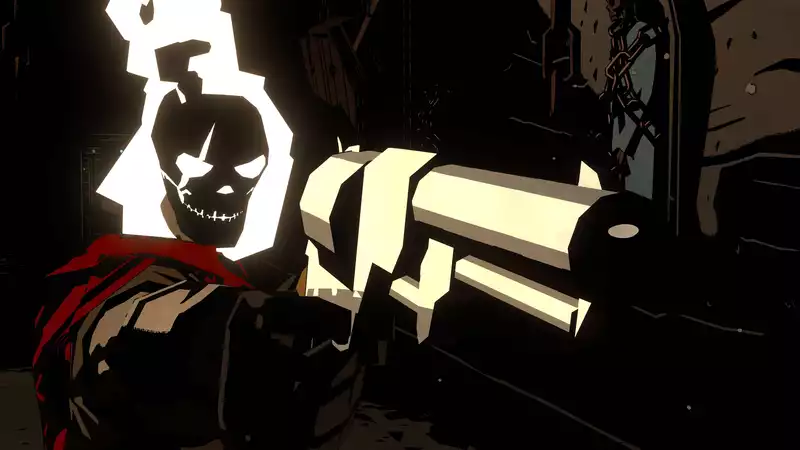

Putting on "iron and sin" makes it a little easier. Curiously, these are not folk bands, but two currencies found in the aftermath of a battle, which can be given to traveling merchants (nameless and mysterious like everyone else you meet) in exchange for guns and item upgrades, or in the latter case, to witches to "purify" them and unlock items The latter can be done by giving it to a witch to "purify" it and unlock items. Had the combat in [West of Dead] not been so skillfully stitched into that enigmatic world, it would not have been so easy to hit "New Run" after a heartbreaker with a landmine. The visuals are attractive, and everything from the objects to the lighting looks like real celluloid art. Hearing Hellboy's voice in the pitch-black underworld feels very Mike Mignola, and the brooding guitar lines, circling crows, and whiskey-laden narration create an authentic atmosphere.

Perlman's narration is frequent enough to keep you constantly aware of the story of West of the Dead. A gunman navigating the afterlife without a compass, trying to figure out how to travel either east or back to "West of Dead," looking back and winking at the camera, snippets of conversations with NPCs, relics found in the catacombs and returned to the witch, and boss fights all "show, don't tell," and give us a glimpse into a backstory that truly lives up to the "don't tell.

It's not just about beating the game; it's about understanding the game. These two motivations keep frustration at bay for longer than it would be possible in a game that so mercilessly ignores the game's sense of progress. But, of course, frustration will eventually come. On the rare occasion that the game itself can be a point of contention, it is the camera work and lighting. Especially when retreating from an arena, the zoom and focal point sometimes go haywire, leaving you with your pinkie up in the air and your eyes glued to the enemy's specs. On the other hand, backtracking because you missed a shadowy, invisible doorway really takes away from the pace of the run.

The roguelike staple of procedural generation is also, of course, a double-edged sword. In some areas, you can run through an area in a few minutes, during which time you can upgrade your weapons and character to a certain degree. If you're unlucky, you'll spend quite a bit of time backtracking or exploring a branch from the first room you missed. Later, when teleportation is available, this dead time is alleviated. Still, at least you are not mechanically moving through the same layout of corridors and arenas.

Other games have explored similar themes and mechanics to "West of Dead," but rarely have they been as cohesive as this. In "West of Dead," the battles, no matter how brutally difficult, always feel fair and always endured for a reason. The information dripping out is cleverly judged, and the macabre developments unfolding in Purgatory, Wyoming, are unintentionally compelling.

.

Comments