It's not often that a game has to be seen to be believed; Viewfinder is both a first-person puzzle game and a digital magic show.

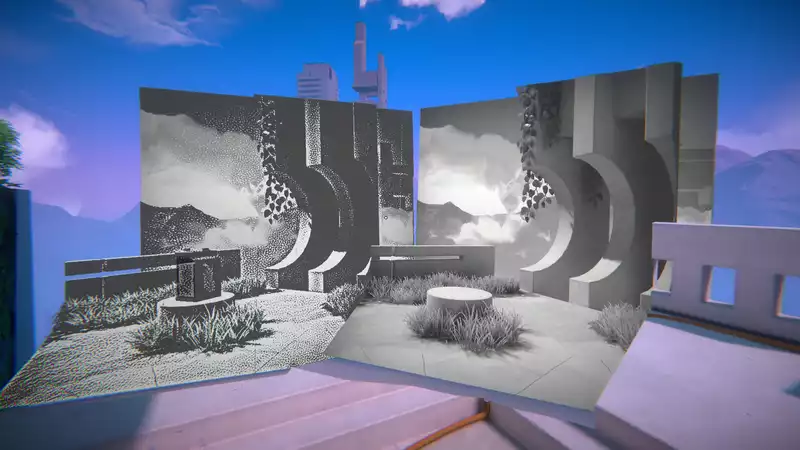

The central gimmick of the game is a magic camera. You take a picture of something, and when you satisfyingly pull out the resulting Polaroid photo from the side, you hold it up and place it anywhere in the world, and everything in the 2D photo instantly becomes part of the 3D environment, drawn directly from the perspective from which you were looking at it. This is phenomenal.

In the simplest example, you can take a photo of a tower, turn it on its side, and place it so that a bridge is built over the gap. Especially if one starts taking pictures of landscapes created by other pictures, one can begin to stack strange and impossible structures to bypass obstacles.

The goal at each level of the game is always the same: to reach a teleporter to get to the next level. It is simple, but not straightforward. Whether it is across a chasm that the teleporter cannot pass through, stuck to the ceiling, or requiring batteries that seemingly do not exist, there is always some wonderful absurdity that must be tackled. When I first realized that the only way to progress through a certain stage was to make a photographic copy of the teleporter and walk through it instead, that was the moment I knew all bets were off in the Viewfinder world.

Discovering the ins and outs of Viewfinder's unique logic is very reminiscent of when we first learned to "think with portals" in Portal; Viewfinder's tricks are just like Portal was back then, playing and it feels like a real discovery.

And there is more than one great mechanic here. The camera is the star of the show, but Viewfinder uses it as a springboard for a variety of optical illusions and reality-distorting tools to poke and prod at your rigid expectations of how the game should look and behave. A seemingly three-dimensional doorway can turn out to be a two-dimensional image on the wall when you approach it; a portal can open up and allow you to step into a completely different art style; a seemingly disparate image on a billboard can become a coherent picture when viewed from the right angle and become part of the world. It can be a part of the world. The best moments in "Viewfinder" have two flavors, because they are the best moments in "Viewfinder". The moment when you realize what great new trick is being played, and the eureka realization of how to get past it.

Because of this variety, there is always something new to discover in each level. I completed the main game, including all optional levels, in five hours, which is not a very long time to just explore the possibilities of the core camera mechanic, let alone the other elements packed into the game. It was a great tutorial for the concept.

Even the photographic mechanics, which are present in some form throughout almost all of the game, feel like they could stretch their wings more. It's fun to mess around with the camera and see how far you can twist the environment, so I'd like to be able to really go wild with a larger sandbox level or a final set of extraordinarily difficult challenges. Just a tool that lets users create their own levels might be enough to draw even more joy out of this great idea.

But if I am complaining that the "viewfinder" is not substantial, it is only because the potential of this game seems so large and exciting. This is the debut title from a small new developer called Sad Owl Studios. In that sense, it is understandable that the game's Achilles' heel is its small scale.

Even if Viewfinder struggles to realize the full potential of its idea, what's here is absolutely brilliant. The brain-twisting puzzles are brilliant, but this is truly a must-see, even if only as a sightseeing tour to see what wonders this team can create in the digital space. If you like to be amazed by games, you should definitely give "Viewfinder" a try. It's a great way to show the game the world from a whole new perspective.

.

Comments