It is this conundrum that haunts Colossal Cave, a new version of the classic text adventure of the late 1970s. While not the first attempt at a graphic reworking of its namesake, that honor goes to 1980's Adventure, and today's game designers still talk about the cave with reverential tones and wistful smiles.

The prose lives on as narration, thoughtfully implemented as the "seeing" interaction that accompanies the cursor. Its presence allows one to appreciate just how faithfully the film is rendered: the level designers at Cygnus Entertainment, led by King's Quest legend Roberta Williams, translate the tangle of floral descriptions into a coherent geographic space, and and deserves credit for giving a natural flow to the initial journey from the forest well house, down the banks of the creek, and through a locked hatch into the underground cave network.

However, the narration also highlights the compromises made by the small development team to take "Colossal Cave" to a new dimension. What 3D art could possibly live up to the idea of "a stunning room with walls like a frozen river of orange stone"? Certainly, that is not what we have here. Then there is the giant's huge dwelling, whose ceiling is "too high to be seen by lamps". However, we can see it now. This fact somewhat diminishes the implied vastness of the scene.

Worst of all is the self-described "breathtaking view" deep underground, an active volcano: in the most extravagant and aesthetic description written for the game back in 1977, Don Woods described "a blood-red glow disguised as an eerie appearance," air "dense with ash sparks," distorted rock, scattering murky light He describes alabaster formations that create "ominous illusions on the walls" by making This new reality is reduced to a feeble Jacuzzi-like setting, especially with respect to the adjacent "steam" geyser. This partial panorama is a sorry substitute for what should be the reward of Colossal Cave, the reward for wading into its most jet-black abyss.

The translation from text to 3D creates problems even in the cave's most intimate moments. The game was a blueprint for the point-and-click adventure genre as we know it today. In the most satisfying cases, Cygnus provides a simple bottle of water early on. Pouring this bottle and replacing its contents with oil might ease the rusty hinges of a door or replenish water in an underground reservoir to grow a beanstalk. There are only a handful of such items in Colossal Cave. More than the number of inventory items one can carry at one time, but not enough to find a specific use for each.

But they share the screen with similar trash that cannot be picked up. Whereas the textual description spotlights a single magazine and directs the eye with a clear purpose, this three-dimensional cave is furnished with a myriad of decorative objects, and the openings are littered with old newspapers and discarded bottles. The metallic sheen makes it easy to discern usable objects from the background, but it still takes some getting used to the arbitrary distinction Cygnus draws between what is important and what can be ignored. This is a problem that the point-and-click adventure genre still has, but from an immersive first-person perspective, it feels starker than usual.

After all, your goal is to find treasures that contribute to your point total. You get a handful of points for finding a shiny object, but you get more for delivering it to the well shack at the starting point. One treasure is a gold nugget the size of a human head, too heavy to carry back up the stairs. Often a tough decision has to be made as to whether or not to drop the diamond for a more innocuous item that might be the solution to a puzzle.

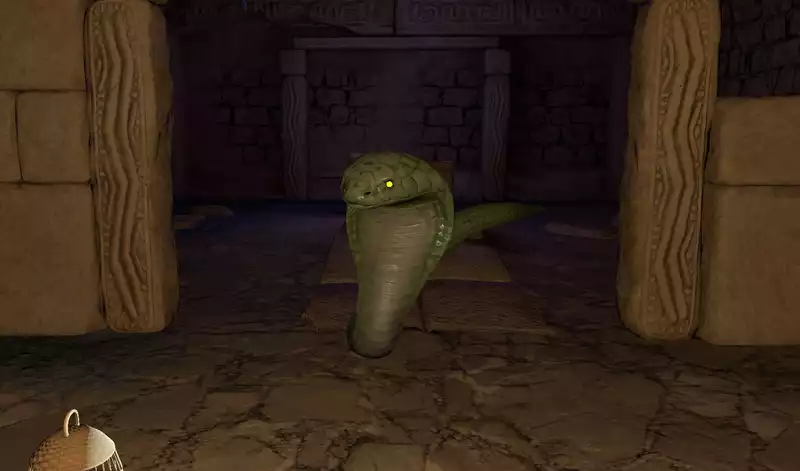

Considering its antiquity, dating back to the dawn of digital game design, Colossal Cave's puzzle logic is surprisingly robust, and much of it spreads naturally and comfortably from the small pool of tools available. However, there are some elements around these puzzles that have not survived the decades so well. For example, dwarves intermittently pop up out of the ground and throw knives at you. Usually they miss, but with a hit rate determined by the RNG, they are killed instantly and sent back to the well house. To make matters worse, resurrection costs money, which is deducted directly from the total score, making the quest for a perfect score a frustrating ambition.

Then there is the maze of Colossal Cave, which was so infamous at the time that it was repeatedly described as "a maze of winding little passages, with a few small holes in the middle, and a few small holes in the bottom. With patience, escape is possible, but agony is inevitable. It is a fact that makes one wonder if parts of the Colossal Cave would have been better off buried deep in the rock. From a design and aesthetic standpoint, there are fairer caves these days.

.

Comments