I don't pay much attention to my humble mouse. I use it every day like a limb and would struggle without it, but when was the last time I thought about a mouse? But "Witch Strandings" puts the peripheral front and center, making the cursor the protagonist and, with very few exceptions, the only way to interact with a doomed world.

At the time of 2019, when discussing what genre "Death Stranding" could be classified under, director Hideo Kojima claimed that the film was a new "stranding game". The hallmark of this new genre is the building of social connections, which in the case of "Death Stranding" was done by delivering packages and connecting disparate communities of survivors. It's like a mix of a walking sim and a community-oriented game like "Stardew Valley" or "Animal Crossing. [Despite being a short, minimalist game in which you control a small ball of light on an adventure to save the forest and the depressed creatures that live there from a witch's curse, "Witch Strandings" must be the sibling of "Death Stranding". The depressed creatures, once human, are in need of friends, who will deliver them food and medicines to cure their ailments.

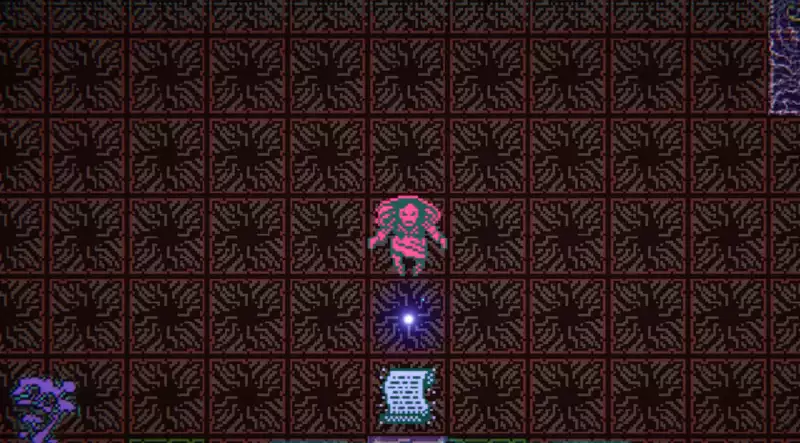

Complicating this quest is the forest itself. Rapids, sharp thorns, quicksand, and evil curses stand in your way and prevent you from moving through this cursed world. There is also calm water, mud, and other terrain that does not block your path, but changes the way you move. If you use the cursor to move through the water, you will notice that it is a little harder to control than usual, as it will continue to float forward even if you stop moving the mouse as it gains momentum. On the other hand, if you get stuck in the mud, you will have to drag yourself out while dragging the mouse.

Despite the lack of elaborate 3D geometry and a stumbling protagonist like in Death Stranding, the game is surprisingly effective at conveying the difficulty of walking through rough terrain. It is also always connected to the world, as every mouse movement veers off in that direction; it may be made up of 2D tiles, but this raw interactivity means that it never feels unspecific.

So many atmospheres are packed into this lo-fi, abstract setup that it is striking how ominous it all feels. When I discovered that the hollowed-out tree was full of red skulls and that anyone who presented them would die, I felt like I was at a ritual murder scene buzzing with evil energy, instead of hanging out in a blocky circle surrounded by cartoon bones. The audio also helped greatly, and the whimsical tunes of the traveling companions were occasionally drowned out by cacophonous layers of noise.

These unsettling flourishes culminate in the approach to the Witch's domain, where the game's title is "The Witch's Witch," and the game's title is "The Witch's Witch. In the context of this bite-sized game, however, it is a huge mass of hostile terrain, and its menacing sounds haunt you the entire time.

After spending several hours exploring the forest, I stopped really looking at the tiles. In my mind, the tiles are transformed into thickets, swamps and lakes, and I need to find a path through them, or at least imagine what path I could make with the right tools. The forest is littered with countless objects, witches pushing back the threats in your path and turning the surrounding area into a safe tile.

Initially, you must drag these objects one by one and place them in the most effective locations. Conveniently, the area the item neutralizes remains clear once the item is picked up. Finally, you get a storage space where you can deposit items for later use, a rare moment when you use the G key on your keyboard instead of your mouse.

With dragging and moving things around for most of the game, the addition of one simple inventory block feels like a genuinely meaningful upgrade. It empowers as much as the fancy new abilities and complex systems, and it immediately makes delivery and exploration so much easier.

Once I had the map in mind, creating permanent paths through obstacles, I raced through the world unbridled. After hours of attention, I was free and wielding my mouse like a madman. As I tore through the forest, I laughed in the face of danger. Thus I drowned in the middle of a lake into which I had accidentally jumped. This was certainly partly the fault of my own recklessness, but Witch Strand must take part of the blame.

You see, the screen only moves when you approach the top or bottom edge, making it difficult to see what lies ahead. This may be designed to preserve mystery, but this limitation does not exist when you move left or right. It becomes more annoying when you consider the large health bar at the bottom of the screen and the frequent notifications that appear at the top, which greatly obstruct your view. When zoomed in, you can pull back to see more of your surroundings, and I found myself mostly playing that way, but still had to move closer to the edge before I could start seeing what was coming up.

Finding new routes across the map or opening up previously blocked areas gave me a nice serotonin boost, but I found myself less interested in the actual quest. Descriptions of abandoned notes and ruined buildings, which could be rebuilt to increase fitness and provide convenient fast-travel options, all feel like snippets of tragic biographies or historical accounts.

I liked the frogs best because I encountered my amphibian companions more often than the others, they usually needed items that were accessible from their location and were easier to energize. I did not learn more about them or develop any kind of bond with them, spoken or otherwise. I only gave the frogs, who were once people, food and drink a few times. In the end, the premise is undermined. I am never prompted to care about the characters I am supposed to help.

Minimalism, however, works in its favor in most cases, making this pillar of the emerging genre look elegant without the multitude of complex systems found in Death Stranding. I scoffed when Kojima began to position this film as a pioneer of a new genre. Now, seeing it again in such a different style, but clearly in the same family of games, I am much more convinced. And I would like to see more.

Disclosure: Strange Scaffold's creative director, Xalavier Nelson Jr. has previously contributed to PC Gamer.

.

Comments